Intention of design is one of the prime reasons architecture still exists in today’s society, even after the recession. The National Park System’s rustic design concepts taps a series of memories for me, who has not visited a national park in decades, with a visit to the West at the young age of 6. I do share a memory with millions of other people, simply because of the signs and structures of the NPS.

Observation Points, The Visual Poetics of National Parks

Thomas Patin, Editor

The first three chapters of Observation Points, The Visual Poetics of National Parks offers an explanation of intent for the park system. Robert M. Bednar’s Being Hear, Looking There, explores the gallery-esque nature of the natural park system. By setting up the ways the view is seen, the audience (or visitors) will have a collective experience of the parks and their grandeur. Likewise, Gregory Clark’s Remembering Zion, explores architecture within the national park, and how the experience of structures has an impact on the memory of the visitor. Finally, Peter Peters’ Roadside Wilderness provides an analysis of the park system over time and major technological shifts. All three chapters provide the reader with an understanding of the immense design opportunity the NPS provided for the western frontier.

When thinking of national park design, the cohesion of the various aspects of manmade elements (signs, roads, structures) could be related to any design project, within or around a space. The architecture of objects, the pathways paved throughout the park, and the way unattended participants use the land is much related to the way-finding and place-making trends of today. Bednar states that the roads, signs, structures and displays serve as a medium, rather than a means, of experiencing the National Park System (3). As an artist who has installed many exhibits, this rings true: the installation is as much of an art, as the art itself. By installing intentional means of viewing the sites, through viewfinders or architectural shelters, the common view for a majority of their audience will result in a common experience. Such a subtle experience allows the viewer to think they are alone in their interaction with the National Park System, yet they are not. Each location, bench, and display has the viewer in mind.

Gregory Clark’s examination of architectural encounters in Remembering Zion explains the intention of shared identities, much like Bednar, yet Clark focuses on the design and scale of the architectural decisions. Rustic Design included native materials, local “craftsmen” aesthetic and a “sympathy with natural surroundings and with the past” (43). The similar memories of the visitors over the decades provide proof that the intentions of the architects of that period to be successful.

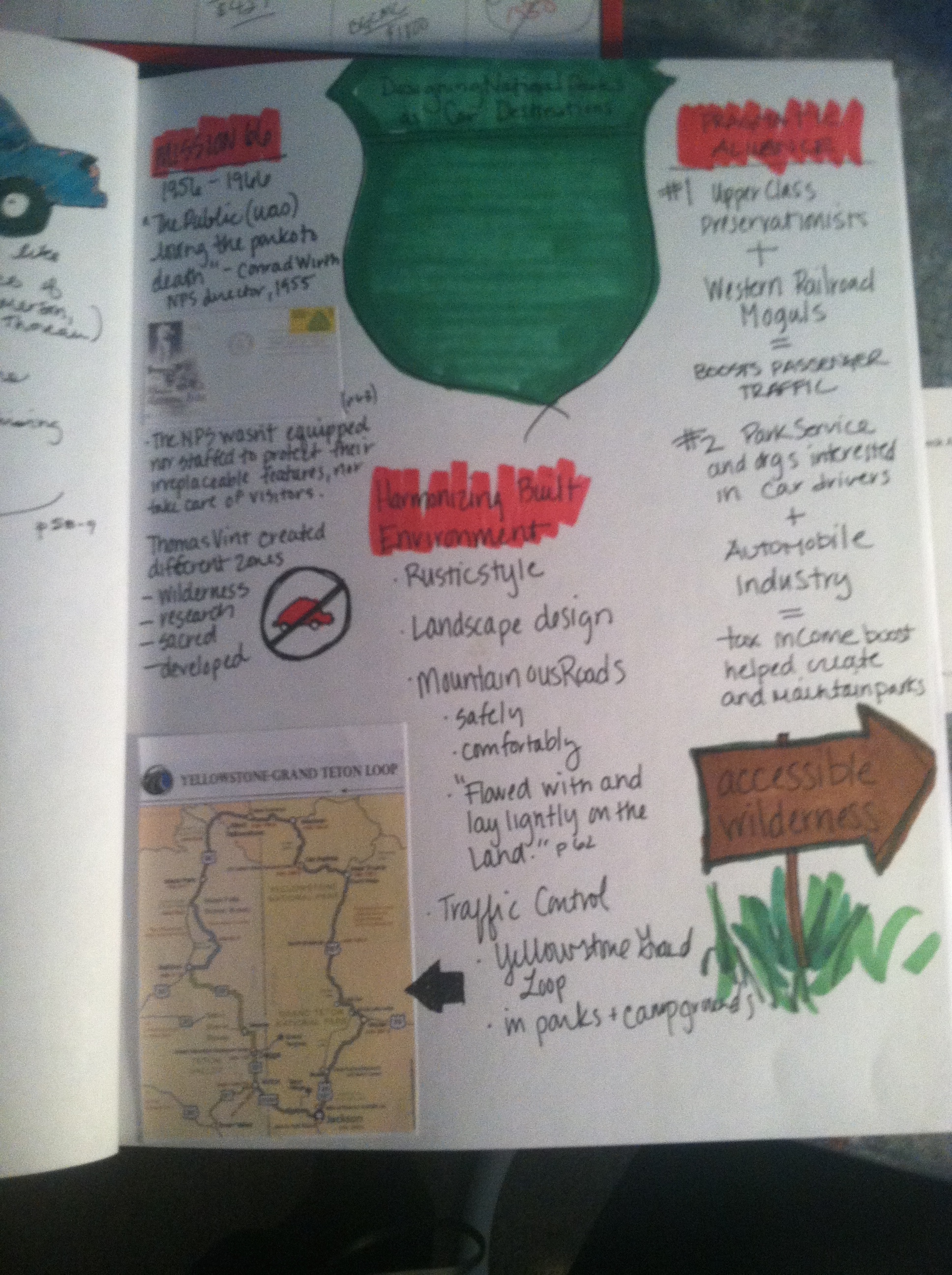

Promotional Materials related to Mission 66

When considering Peters’ chapter on the examination of design during the 1950s and 1960s, the “concept of passages” provides a large context of the growth of automobile use, and its impact on the environment, especially in relation to the fragility of the National Park System. There was a complex system that included preservationists, railroad companies, park service entities and the automobile industry, therefore the considerations were not simple. Conrad Wirth, the 1955 NPS director, said, “The Public (was) loving the parks to death,” therefore the way finding had to be crafted in a way that was not damaging to the environment, nor blocking the accessibility to the public.

This dilemma reminds me of the house my parents built in rural Minnesota upon my graduation from high school: they purposely designed it so their children can come back home (as adults), yet they will not stay for long. While this humorous connection seems ill placed in this examination, there is some truth. A home is designed from scratch, to work within a landscape that has existed centuries before the structure. This aesthetic cohesion is felt by the users, loved by the visitors, and remembered as the years go by. Granted, in the case of my parent’s home, they are still in need of time to be… just be, without the expense and energy of being a host. They would have to do extra work to keep the house in order, repair broken stuff (assuming their grandchildren are rascals) and planning for more people to come visit. It would deplete the resources they have to offer, therefore would not be sustainable. Luckily, because of the way the home was designed, very little needs to be said about the length of a stay, resource contributions of the visitors or the boundaries of activities.

When looking at the intentionality of the National Park System, with their ways of addressing accessibility, communal memory and environmental sustainability, I would consider the complexity of any public park, and their use of aesthetic and utilitarian resources. In the Sartell Mill Project, my current project, we are placing four different sculptures within the landscape of an 11 acre park along a creek emptying into the Mississippi. There are fascinating discoveries throughout the land, yet without intention, the developers may simply create a park with a bunch of plopped objects to “meet the needs of their community.”

I had to walk through thick weeds to get to this view. Accessibility is key, but the question is "to what extent?" Watab Creek, Sartell, Minnesota 2014

The fact that the community invited me into the project, to create an artful acknowledgement of history and tragedy, has brought me to consider every aspect of the park in the placement of the art pieces. We considered natural features (the Watab creek and Mississippi), as well as the historical use of the Watab, with a kiddie pool and playground. While the upgrades of the park is dependent on the approval of a tax increase and the allocation to focus on the space, the fact that they are even willing to consider art installations in the planning is rare in a greater Minnesota town.

That being said, the fact that use of the space is considered, by the artist, is an oddity from the city’s point of view. Not the fault of any one entity, the integration of art in projects is usually nonexistent. The traditional practice is to include art as an embellishment, or as I like to call it, “The earrings with the dress.” It becomes the point of focus, yet more resources are usually put into that dress, and can also steal the show! I believe that the art in a public park should have an intention, that works with the space, purpose and users. Whether the work blends with the space, like the Rustic style signage of the NPS, or bold like the 1950s park structures, the audience should be considered not just when the piece is installed, but throughout the time that the object is in existence.

This was written as part of my graduate work at the University of Minnesota, Arts & Cultural Leadership. The course is Revitalizing Environmental Reform: Reimagining the Arts of Public Parks with Roslye Ultan (Oct 20 - Dec 9, 2014).